“If you want to argue with “science” as you refer to it, you are welcome and encouraged to do so…but bring your superior evidence and data to the argument!”

Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty — some most unsure, some nearly sure, none absolutely certain. pic.twitter.com/TCMuP9GM8J

— Richard Feynman (@ProfFeynman) July 13, 2018

One of the most revered Scientists of our day, the late Dr. Richard Feyman. Photo courtesy: PopularMechanics.com

Science can be tricky. However, just like with everything else, use proper judgement, and don’t outrun your common sense.

I want to preface a recent insightful Facebook conversation on this with a couple things…

According to Wikipedia,

“Richard Phillips Feynman was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, and the physics of the super-fluidity of super-cooled liquid helium, as well as in particle physics for which he proposed the parton model. For his contributions to the development of quantum electrodynamics, Feynman, jointly with Julian Schwinger and Shin’ichirō Tomonaga, received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965.”

It’s okay. I know you’re eyes glazed over reading that paragraph. All you need to know is yeah, Dr. Richard Feynman was a super smart dude. “…varying degrees of certainty” are the keywords to pay attention to in the Tweet. He was a true student of Science, using the Scientific Method, and trying to be as objective and unbiased as any human can be. He had a passionate curiosity of how all things worked. A true blue scientist. I highly recommend Dr. Feynman’s book titled, “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character“. It’s not a very technical read, goes fast, and is fascinating.

Wondering how to how to spot BAD Science? Try this book titled, “Bad Science: Quacks, Hacks, and Big Pharma Flacks“ by Dr. Ben Goldacre. Dr. Goldacre’s humor and sarcasm goes a long way in getting through this one.

Okay, now that that’s over, let’s get to this week’s post…

I wanted to share a recent Facebook conversation I had with a couple gents. One I will name “Coach”, so as to not put his name on blast. Do you believe this statement: “…science is today’s religion. Ppl take it as, fact. If you think science is fact your horribly mistaken.”?

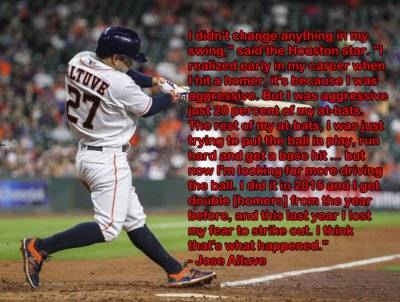

I interjected in the following conversation, but mainly to confirm Jason O’Conner’s points. He did a great job of picking apart this objection. Feel free to use this as fire power for those coaches justifying NOT using science to mold effective swings. At the end, I’ll put proof in the pudding. The conversation went a little like this…

Coach:

“…yes u can argue with science. Science is religion not fact. Its guessing and testing not thinking and proving. Very little is proven fact in science. Science is only science until better science comes along. For example. The science of hitting….. there’s ppl out there that say he wasn’t completely right. Then there will be someone new saying the same of your doctor…..i find it funny scientists who can’t hit anything telling ppl the proper way to hit.*”

Jason O’Conner:

“Science is neither religion or guessing and testing. It is the discipline of seeking knowledge in pursuit of the truth and understanding. Whether being applied to medicine, the weather or the baseball swing, that understanding is only as good as the currently available information (data), and yes a process of observation, testing and retesting as tools improve necessarily updates our knowledge and improve our understanding. It does not rely on faith as religion does. It relies on evidence and data. “Hard anywhere” is a result. It doesn’t explain or teach how in fact one hits the ball hard anywhere consistently. That requires some understanding of how the bio-mechanics of the swing works and can be made most efficient for each player. If you want to argue with “science” as you refer to it, you are welcome and encouraged to do so…but bring your superior evidence and data to the argument!”

Coach:

“…science is today’s religion. Ppl take it as, fact. If you think science is fact your horribly mistaken…And i equate science to religion because ppl believe in it like a, religion. Examples being global warming, salt. Salt every day goes back and forth on being good or bad for u. Some think its bad…. others good….. And they all think that way because science told them to. That’s my problem with science. And, again……when better science comes along your science will no longer be science…… like i said. Hitting was figured out scientifically in the 70’s…….But today’s science said they were wrong. Yet they hit better back then.”

Jason O’Conner:

“…better science cannot come along and replace anything. Science uses better information and better data to improve understanding. Usually this happens as a result of technological advance. This is a pointless debate here. But of two things I am convinced:

- Your problem is not with science it is with people who may have referred to science to argue a viewpoint you disagree with…science requires critical debate of evidence to come to the most likely conclusion and

- As a generality, the elite athletes of today are superior to those of 30+ years ago. Trout would be the best hitter in any era. That is my opinion. Olympic athletes use bio-metrics in every aspect of their training, and there are few world records more than 10 years old.”

*I have a big problem with coaches who are arm-chair quarterbacks. Saying something like, “I find it funny scientists who can’t hit anything telling ppl the proper way to hit”…is laughable, and a total slap in the face to hard working scientists like Dr. Richard Feynman. This statement comes from a coach possessing a stubborn Fixed Mindset. If every arm-chair QB would seek the truth like a Dr. Feynman, Dr. Serge Gracovetsky (The Spinal Engine), Dr. Kelly Starrett (Becoming A Supple Leopard

), or Dr. Erik Dalton (Dynamic Body

), they wouldn’t chronically suffer from foot-in-mouth disease.

Here’s a quote from Dr. Ben Goldacre that packages this coaching paradox nicely:

“I spend a lot of time talking to people who disagree with me – I would go so far as to say that it’s my favorite leisure activity – and repeatedly I meet individuals who are eager to share their views on science despite the fact that they have never done an experiment. They have never tested an idea for themselves, using their own hands, or seen the results of that test, using their own eyes, and they have never thought carefully about what those results mean for the idea they are testing, using their own brain. To these people “science” is a monolith, a mystery, and an authority, rather than a method.” – Ben Goldacre

I’m 100% CERTAIN there is BAD Science out there. But coaches, it’s your job to weed out the good from the bad. Just because 20% of Science may be bad, doesn’t mean we should not listen to the other 80%. Don’t be a fool. Knock the chip off your shoulder you may have about Science. Don’t outrun it, but exercise common sense. Please, please, PLEASE!

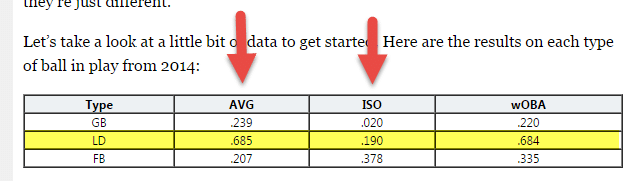

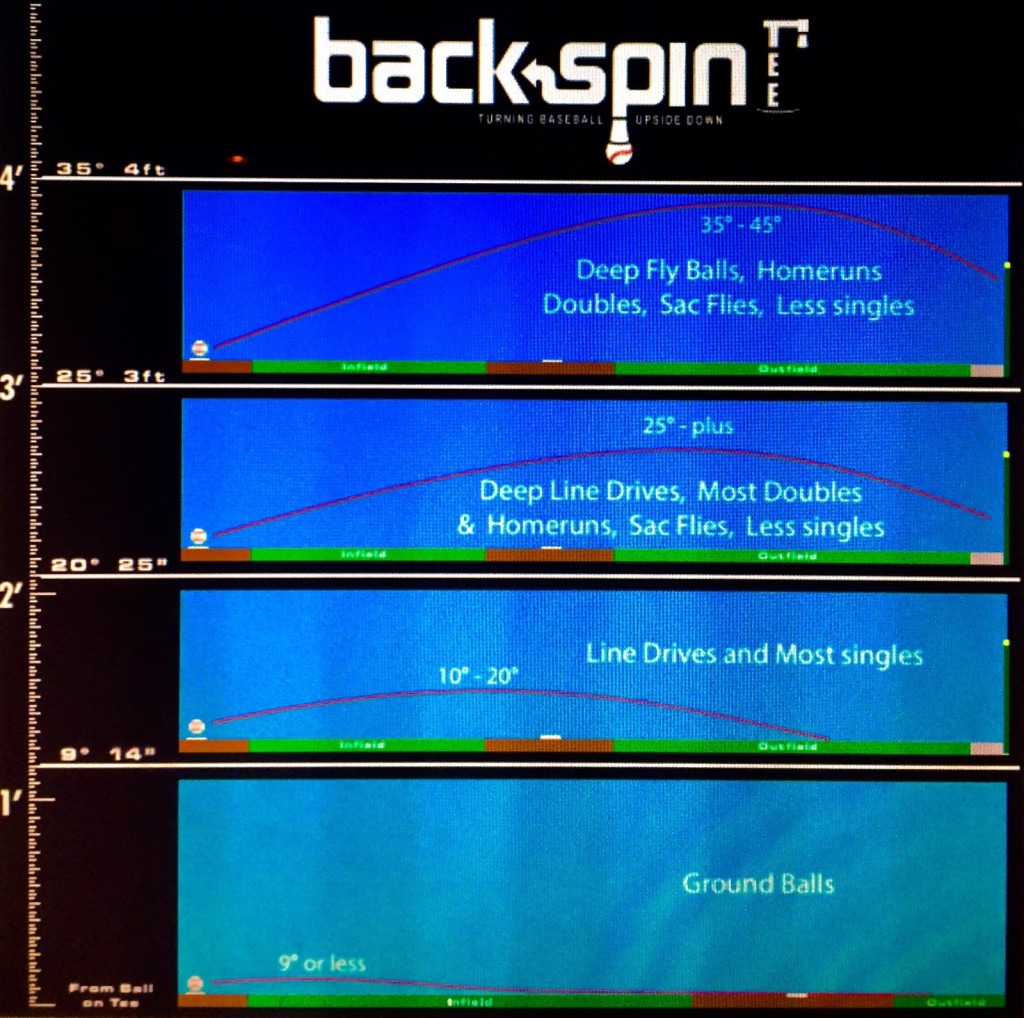

You can eat soup with a fork, knife, or spoon, but only one way is more effective. Teaching hitters is the same. There are hundreds of ways to teach hitting that’s for certain. However, applying human movement principles that are validated by REAL science to hitting a ball, NOT because-I-said-so “bro-science”, is the pathway to power.

Coaches, have a higher standard for your hitters. WHY? Because your hitters are counting on you.

Success leaves clues. I wanted to share a couple of my most recent testimonials received from parents (within the last week or so), unsolicited by the way. Words can’t express the gratitude I feel on a weekly basis, almost daily, from parents and coaches sharing how these human movement principles are helping their hard working hitters…enjoy!

Josh, text message after coming up to Fresno from Los Angeles to hit for 2-hours, sons: Matt (Senior HS), Jonny (8th Grade), & James (6th Grade) come up…

“Thank you again for working with the boys. Both James and Jonny crushed a hit last night. Jonny went 2-for-2 with 2 triples. James got his first double in a long time. Field we played on had no fence so ball kept rolling…U should have heard the convo on the way home. How they told their teammates their hitting instructor is the GOAT. Hilarious”

Chris, email about son Aidan (11yo) who has been working with me in my online video lesson program The Feedback Lab since 2017

“Joey, a sincere note of thanks for your guidance over the past two seasons in helping Aidan at the plate. The All-Star team of which he’s a part won the State 11u tournament this past weekend and now moves on to the Midwest Region. Since the team was selected, he’s worked his way up from batting 10th in the first tournament to 5th in the State Finals. He’s gone 10/25 (.400) with 8 singles, 2 doubles and 8 RBI. The last double came with 2 outs in the bottom of the 6th, bases loaded, and our team trailing 3-0. Pretty pressure-filled situation being down to the last out with the season on the line. He drove in 2 runs on a line drive down the left field line and went on to score the winning run.

In no way is this meant to be boastful. Sure—we’re really proud of him, but I truly believe the work he’s put in based on your instruction has given him the confidence as one of the smallest kids on the team to hit the ball with authority against any pitcher he faces. Many thanks!”

Peter, email about son Ethan (9yo) who has been working with me in my online video lesson program The Feedback Lab since February of 2018.

“Thanks Joey, great feedback and analysis as always. The great part is that I’m also learning from you as we continue along. As I was getting ready to send you the last video I was seeing a lot of what you discussed in your analysis; keeping the shoulder angle and showing numbers to landing, and the top hand coming off way too soon. But I was struck by the consistency with his swing, every one had good barrel angel at landing, head movement after landing is way down and as you mentioned you can really see a much more confident swing! Thanks again Joey, we couldn’t be happier! Looking forward to getting back at it! Talk again in a few weeks!”

Jason, email about son Bleau (12yo) who flew from Knoxville, TN with his best friend Jaser (11yo) and his family to hit, catch some Cali sun, and MLB baseball games. We hit for 10-hours spread out over 3 days.

“Joey, we had a wonderful dinner tonight down in Fisherman’s wharf. I asked the boys what their favorite part of the trip was thus far. Bleau said that ‘Joey is my favorite part’. Thank you for coming through and investing in him. We look forward to meeting your family.”

And last, but certainly not least, an updated on Hudson White, who if you remember was showcased in this post highlighting his performance at the National Power Showcase…

“This year he was a freshman on varsity at Byron Nelson high school. He was starting 2nd and 3 hole. He led all north Texas in hits most of the season and finished 7th overall with 45. He was hitting the ball hard somewhere! Hudson was named District 5-6A Unanimous Newcomer Of The Year and All – Area Newcomer of the year finishing 7th in area with 45 hits, 25 RBI, 21 runs, 16 SB

He also just got back from the Wilson Midwest wood bat championship where he was names MVP for hitting two home runs. He went 9-18 and only 1 single. The rest were doubles,triples and dingers! Here’s his MVP interview:

https://twitter.com/

martinbwhite/status/ 1007094716427653120?s=12 He has been on a tear hitting 6 home runs in the last 3 weeks with either wood or an old rusty metal bbcor bat. Just an FYI update to all the haters and naysayers

its the Indian not the arrow. I appreciate your help and instruction. The proof is in the pudding.” – Marty White, email update about his son Hudson “The Hawk” (16yo)

TRUE or FALSE: “If you think science is fact you’re horribly mistaken”…FALSE. Saying Science is just a “glorified opinion” is nonsense. If that’s truly what you think, then you’re obviously spending time on the wrong things. The little bit of BAD Science shouldn’t take away from the majority of good out there. Coaches, please use some common sense, and as always test this stuff out for yourself – don’t just take my word for it. And I think true-blue scientists like Dr. Richard Feynman would agree.